Subaru owners are a green bunch. They tend to bike, camp and kayak more than other drivers and inordinately live in the parts of the U.S. with the toughest emissions mandates. The company plays to this ecological image by producing more than 1 million vehicles each year without sending any waste to landfills. Yet the Subaru set can’t buy a battery-powered version of its favorite car.

Today’s Subarus run exclusively on fossil fuels. Later this year, the company plans to introduce a plug-in hybrid version of its Crosstrek SUV, combining gas engines with electric motors. A fully electric car is still years away.

“If we put one out now, we’re going to be competing in the teeth of the market with everybody else,” Subaru Corp. U.S. Chief Executive Officer Tom Doll explained in an interview. “This way, we can let them kind of sort it out, then we can come in.”

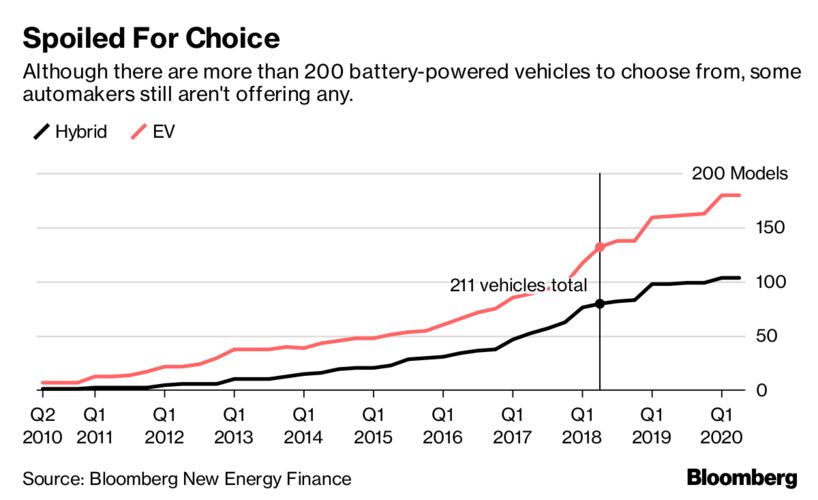

Subaru is among a small group of automakers setting a casual pace in the global race for electric vehicles. Mazda Motor Corp. is on a similarly relaxed timeline—at least two years from introducing a battery-driven motor. Mazda could not be reached for comment, but the company has said the relative efficiency of its gas-powered cars afford it the luxury of moving slowly and deliberately. The far larger Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV currently offers just two vehicles featuring battery technology: the Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid minivan and the all-electric Fiat 500e.

These laggards appear content to let other research and development departments perfect the technology while consumer demand slowly merges with accelerating emissions mandates. Demand for electric vehicles outside China is weak, with battery-powered models accounting for only one in 50 or so vehicle sales globally. Battery technology is still expensive, and charging infrastructure is sparse in many parts of the world. Above all, it’s hard to find examples of manufacturers wringing profits from the electric revolution right now.

Slow sales haven’t deterred others from charging into what may prove to be the auto industry’s biggest growth story in decades. Volkswagen AG is in front, with 17 battery-powered models available right now, followed by Bayerische Motoren Werke AG’s 13 plug-in vehicles. Even a more cautious U.S. automaker such as General Motors Co. expects to have 20 all-electric options by 2023, including seven different sport utility vehicles.

A slow roll to electrification can make sense. An automaker gets to save in the near term by allowing rivals to pay for electrification R&D. In a few years, when the costs of batteries have dropped drastically, a latecomer can then try to hammer out deals with the best suppliers and be right back in the electric race.

“That is the bet,” said BNEF analyst Colin McKerracher. “Basically, they think they can wait and see.”

Fiat Chrysler boss Sergio Marchionne went so far as to beg customers to not buy the all-electric 500e, noting in 2015 that his company was taking a $14,000 loss on every one that silently coasts out of a dealership. More recently, he questioned the wisdom of EV production under current circumstances: “I don’t know of a (business) that is making money selling electric vehicles, unless you are selling them at the very, very high end of the spectrum,” Marchionne told a crowd at Detroit’s annual auto show.

While skipping the infancy of electric vehicles has advantages, there are risks to being late. Subaru, for instance, could tarnish its halo among the environmentally sensitive drivers now placing hundreds of thousands of reservations for emission-free Teslas. Latecomers also risk missing out on recruiting top electric engineers and establishing vital battery-supply deals.

Battery prices have fallen by 79 percent in the past seven years, a pace that will make electric vehicles cost-competitive with internal combustion cars by 2024, according to BNEF. “Once this happens, things will shift quite quickly,” McKerracher said. “Even now, you’re starting to see more and more automakers say, ‘Yes, we can actually make money on these things.’”

No less a skeptic than Marchionne foresees demand accelerating quickly. He expects that by 2025, more than half of all vehicles sold will be powered, at least in part, by batteries or fuel cells, and he recently gave the green light to build hybrid drivetrains on all models of Ferrari, another company he helms. Fiat is also steering its Maserati brand squarely into Tesla Inc. territory, with plans for a sinuous, all-electric sports car that will zip up to 196 miles per hour.

The thesis that an electric laggard can just order the right package of parts and quickly get back in the race has one glaring weakness: Back in 2003, Tesla filled the lonely role of startup automaker; today, a rash of companies is trying to sell electric vehicles as a way to break into the industry. The commodification of batteries and efficient, reliable electric motors is lowering the industry’s barriers to entry.

Workhorse Group, a Cincinnati-based manufacturer, is now taking orders for what it bills asthe first “plug-in range extended electric pickup truck.” The rig, which took three years to develop, is largely an exercise in parts shopping: The gasoline engine comes from BMW, the battery from Panasonic Corp., the chassis from Detroit’s own Quality Metalcraft Inc., and the differentials from Dana Inc., an Ohio-based supplier that sells similar parts to General Motors.

Workhorse CEO Stephen Burns said the all-in cost to design and bring the truck to market was a number “that a traditional car guy would laugh at.” The hybrid pickup will retail for $52,500.

The most popular truck in America, Ford’s F-150, won’t have battery power until 2020. “It’s just one of those classic things where the incumbents have such a thing to protect,” Burns said of Ford’s slow-roll to battery-powered trucks. “Honestly, we’re much more worried about Tesla coming out with a pickup.”

Subaru, meanwhile, will make its late debut as the manufacturer of a battery-powered vehicle by co-opting hybrid technology from Toyota, which owns almost 17 percent of its shares. That partnership and Subaru’s relatively small size enables company leaders to believe they can afford to be patient.

“I’d rather be last in and get it right,” said Doll, Subaru’s U.S. chief, “than be first in and destroy my brand image and reputation.”

0 Comments